An easy decision, but Fed watches for gathering clouds

Key Takeaways

- As it continues to prioritize fighting elevated inflation, the Fed raised its benchmark policy rate by another 75 basis points.

- The Fed appears to be tolerating signs of a cooling economy as it recognizes the imperative of regaining credibility and taming generational-high inflation.

- While longer-dated yields are likely capped as they signal a slowing economy, we believe shorter-dated yields may surprise markets to the upside as the Fed front loads additional rate hikes.

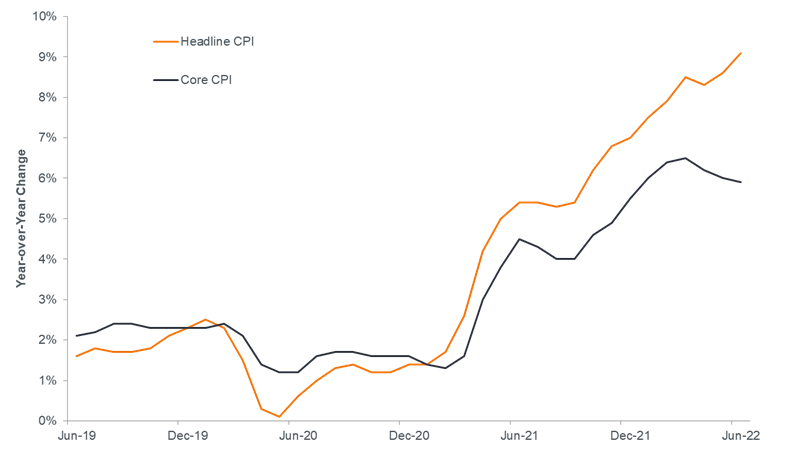

As had been widely telegraphed, the Federal Reserve (Fed) raised its benchmark overnight lending rate by 75 basis points (bps) on Wednesday. We consider this move necessary as the Fed has been forthright in its prioritization of taming multidecade-high inflation. In contrast to May’s 50 bps hike and June’s 75 bps increase, the central bank is now having to deal with rising tension between uncomfortably high inflation and incipient signs of a slowing economy. Still, after having misdiagnosed the malady of persistent – and accelerating – inflation during the latter half of 2021, Fed officials are not likely to take their eye off the ball until there is clear and convincing evidence that rising prices are moderating. With headline inflation – which inordinately effects the purchasing power of a large chunk of the U.S. population – still above 9.0%, we are not there yet. Given this, despite 225 bps of hikes thus far in 2022, we still believe that U.S. monetary policy has yet to reach peak hawkishness.

Tempering Forward (Mis)guidance

The past year has provided ample evidence that the Fed’s objectives of providing forward guidance and being data dependent can, at times, be incompatible. Last December, the Fed’s own estimate of where its policy rate would reside at year-end 2022 was 0.875%. Fast forward seven months and it has already crested 2.50%. The data won out. Forward guidance may have worked during the decade following the Global Financial Crisis – a period characterized by doggedly low inflation – but not during an era of historic fiscal and monetary expansion. While – as the Fed pointed out– continued supply constraints and the war in Ukraine have contributed to inflation, a considerable amount is owed to higher aggregate demand.

If the recent shift in rhetoric is any indication, Fed officials have learned their lesson and now place greater emphasis on data over maintaining a preordained path laid out by earlier guidance. In addition to keeping policy properly calibrated, the ascendency of data, in our view, should have the added benefit of helping the Fed repair its damaged credibility. That said, we believe the Fed will move in an orderly fashion and avoid overreacting to any one data point. The U.S. economy is remarkably complex and there can be considerable noise in higher-frequency data.

Speaking of Data Points

The past three rate decisions were slam dunks. Consumption was strong as the economy continued its emergence from the pandemic and household finances were buoyed by a raft of government programs. By many measures the U.S. economy remains healthy. Even the first quarter’s annualized gross domestic product of -1.6% can be positively spun as the contraction was owed to a boost in imports from purchase-happy consumers – itself a sign of a recovering economy. Still, overall consumption has slowed from its post-lockdown peak. Given consumers’ commanding share of the economy, their willingness to put up with higher prices across major categories – and increasingly higher financing costs – bears close monitoring.

Other data indicate that higher rates along with other tightening measures may be starting to bite. Monetary policy tends to have a lagging effect and while it’s only been four months since the Fed began raising rates and reducing its balance sheet, this entire cycle has taken on a truncated nature. Given the speed of the recovery and the degree to which aggregate demand – and inflation – overheated, so too may the dampening effects of tighter policy arrive sooner than anticipated.

Evidence on that front is beginning to emerge. Core inflation has fallen from 6.5% to – an albeit still painful – 5.9% and headline inflation – at 9.1% – may eventually follow suit given the 17% decline in the price of West Texas Intermediate oil from its recent peak. The labor market is also showing signs of losing steam as the four-week average of initial weekly jobless claims has risen from 170,000 to 241,000. That level is still indicative of a healthy labor market but given the degree to which jobs are used as a lever to calibrate the economy to changing conditions, this figure also merits further observation.

Core Consumer Price Index (CPI) Dips; Will Headline Follow Suit?

Despite recent declines, core inflation remains worryingly elevated and we believe this could lead to more restrictive policy than what is already priced into markets, should it not begin to subside.

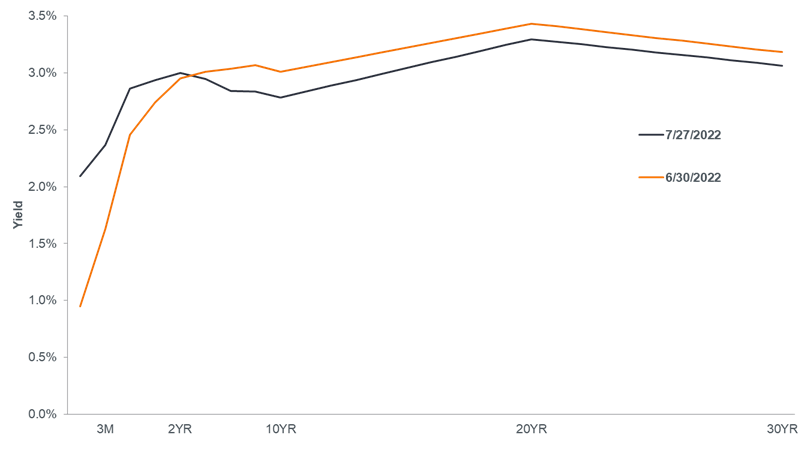

The Curve Reacts

Bond prices have been working overtime to reflect investors’ expectations for the future path of policy rates and recent economic developments. These myriad signals are manifested in the changing shape of the U.S. Treasuries yield curve. Plummeting yields on longer-dated bonds indicate that the market is taking the Fed at its word that it will not take its foot off the pedal until confirmation that inflation is receding toward the central bank’s preferred range. We share this view and believe that, in contrast to only a few months ago, longer-dated Treasuries may prove less volatile over the near- to mid-term, with the yield on the 10-year note likely capped at 3.0%.

U.S. Treasuries Yield Curve Fluid

While longer-dated maturities had exhibited higher volatility, we believe shorter-dated bonds how have greater potential for price swings until a clearer picture on the path of core inflation emerges.

The path of shorter-dated yields over the next few months may be less certain. The market has given the Fed a chance to regain credibility, and to reward that trust the central bank won’t stop tightening until inflation has been defeated. Consequently, we believe that the Fed will front load future rate increases. This aligns with our view that policy has yet to reach peak hawkishness. Futures markets currently imply the upper bound of policy rates reaching 3.5% in December – the equivalent of four more 25 bps increases and roughly the same level it was at end of June. Even if this is where the overnight rate ultimately resides, we believe it may be reached sooner than later – a view at odds with current market pricing – to allow tightening conditions to take full effect before the Fed decides how to proceed.

With the market giving credence to the Fed’s ability to reel in inflation, we believe that investors should reconsider exposure to more rate-sensitive bonds. These securities were punished earlier in the year as investors grimaced that the Fed may once again be behind the curve with respect to inflation. In contrast to much of the pandemic era, yields have reset at levels that have the potential to offer higher income streams and greater diversification.

While this meeting was fairly predictable, we believe September’s conclave could be considerably more impactful. The Fed will have several more weeks of data to decipher and we will watch closely as to whether additional signs of an economic slowdown shift the balancing act from its current preference of taming inflation toward possibly growing concerns of igniting a labor market recession.

Headline inflation is a measure of the total inflation within an economy, including commodities such as food and energy prices (e.g., oil and gas), which tend to be much more volatile and prone to inflationary spikes.

Gross domestic product measures the value of the goods and services produced in the economy.

Aggregate demand is a measurement of the total amount of demand for all finished goods and services produced in an economy.

Core inflation excludes food and energy prices because they vary too much from month to month.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) is an unmanaged index representing the rate of inflation of the U.S. consumer prices as determined by the U.S. Department of Labor Statistics.

U.S. Treasury securities are direct debt obligations issued by the U.S. Government. With government bonds, the investor is a creditor of the government. Treasury Bills and U.S. Government Bonds are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the United States government, are generally considered to be free of credit risk and typically carry lower yields than other securities.

A yield curve plots the yields (interest rate) of bonds with equal credit quality but differing maturity dates. Typically bonds with longer maturities have higher yields.

The overnight rate is the rate at which banks lend funds to each other at the end of the day in the overnight market.