On the future path of rates: Pause does not equal pivot

Dan Siluk and Jason England, Kapstream Capital

Impact of higher global bond yields

-

The Federal Reserve (Fed) acknowledged that “cumulative tightening” will be a factor in future rate decisions, but we still believe the central bank will be forced to remain hawkish longer than it expects.

- While we believe a pause in rate hikes by mid-2023 is possible, we expect it would be an effort to measure the lagging effects of earlier hikes rather than the first step toward a dovish pivot.

- Although the resetting of monetary policy has been painful, over the longer term, the return of positive real yields and the potential diversification benefits to riskier assets should prove beneficial to bond investors.

The Federal Reserve’s (Fed) Wednesday decision to increase the upper limit of its benchmark overnight lending rate by 75 basis points (bps) to 4.00% was easy for the market to anticipate, given the degree to which U.S. central bank officials have telegraphed their priority of getting generationally high inflation under control. Where we think the market may be misreading the Fed, however, is the monetary authority’s willingness – or ability – to take its foot off the gas.

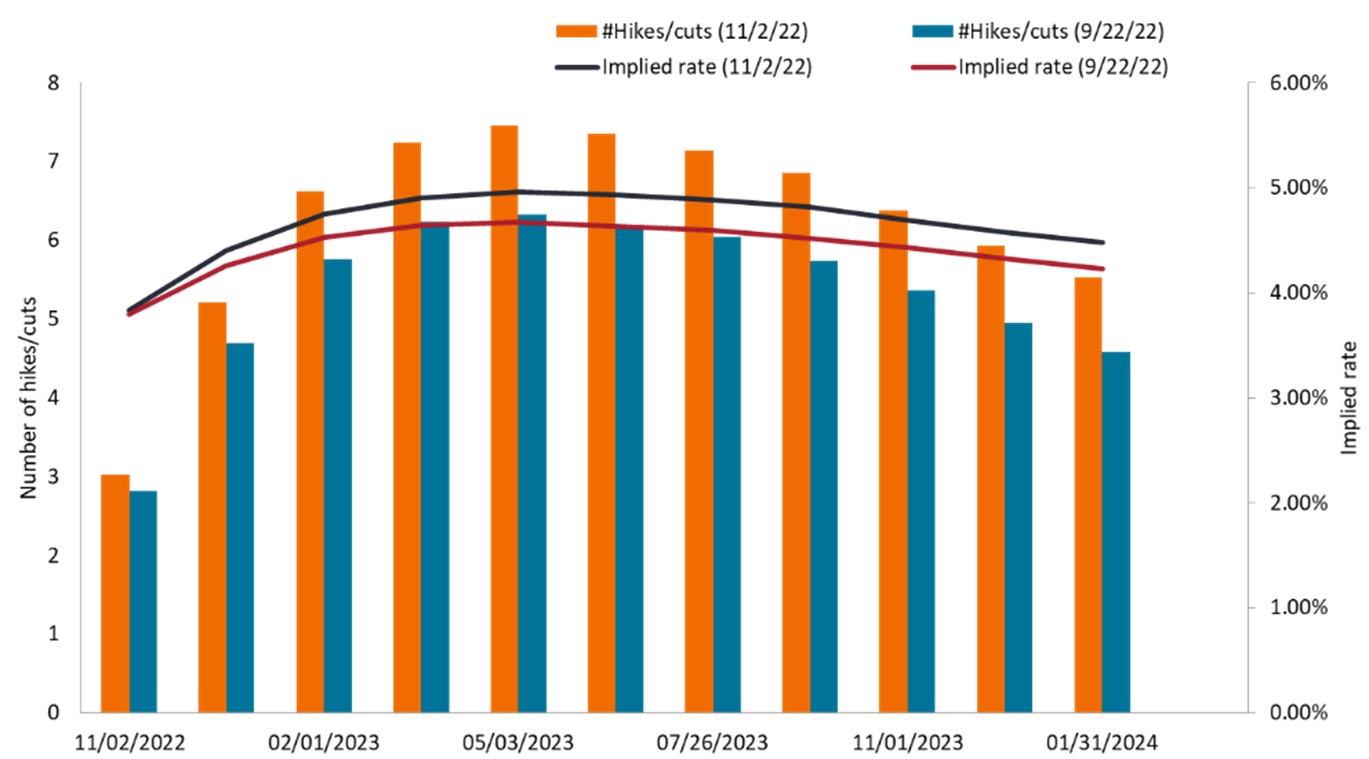

Using futures prices as a yardstick, expectations are coalescing around the view that the Fed’s policy path may peak by as early as next May and that a rate cut could be possible soon thereafter. In fact, after today’s statement, the futures-implied rate path through mid-2023 dipped, due in part to the insertion of language that “cumulative tightening” would be factor in future moves. We consider it wishful thinking on the part of shell-shocked investors that all of the pain associated with the resetting of rates to more “normal” levels is behind us.

Expected trajectory of Fed funds rate based on futures market prices

We don’t agree with the futures market’s view that a mid-2023 pause in rate hikes will inevitably lead to a dovish pivot.

Source: Bloomberg as of 2 November 2022. Note: For normalization purposes, estimates based on 2 November include the 75 bps hike that occurred at the November meeting.

We think only a material deterioration of economic conditions, likely brought on by an exogenous event, would cause the Fed to abandon its hawkish resolve. This is not our base-case, however. We, too, expect the path of policy rates to pause within the next several months but, importantly, pause does not mean pivot. As rates rise at a pace not seen in a decades, we’ve been consistently reminded of the long and variable lags of such actions. It’s our view that a mid-2023 pause would serve the purpose of allowing the Fed to measure the effects of previous “cumulative tightening rather than sending an “all clear” signal.

More work to be done

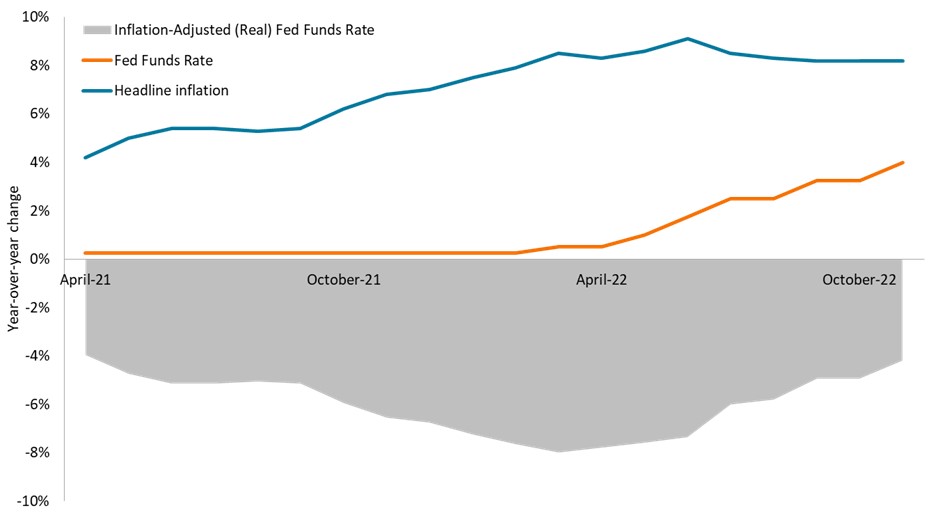

Driving our view that a pivot is unlikely is the magnitude of the task at hand. Given the added nuance of today’s statement, we may even be more circumspect than the Fed. Despite the equivalent of 15 25 bps rate hikes this cycle, the inflation-adjusted – or real – overnight policy rate1 remains below -4.0%. If the goal is to push borrowing costs into positive territory – i.e., no more free money in real terms – there is much work to be done.

Other measures also hint at the need for the Fed to remain vigilant. In a service-based economy such as the U.S., wages play a pivotal role in driving inflation. Fed officials have long sought to stave off a self-fulling wage-price spiral. The annual change in real average hourly earnings is -3.2%. At that dismal level, workers are likely to capitalize on a still tight labour market to press for higher pay to maintain purchasing power. And while shelter’s sizable contribution to inflation may start to wane once lease renewals fully incorporate this year’s uptick in prices and higher mortgage rates cool the housing market, energy prices again appear to be on the march as global crude production is curtailed.

Inflation-adjusted Fed funds rate

If the goal is to tap the breaks on the economy by sending short-term borrowing costs into positive territory, policy rates will likely have to keep climbing.

Source: Bloomberg as of 2 November 2022.

Grasping at straws

We think much of this meeting’s sentiment aligns more with our cautious view than it does with the broader market’s more optimistic interpretation. Since their most-recent bottom in mid-October, U.S. equities have rallied over 9.0%. In recent sessions, the bond market as measured by the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Index has notched modest gains as well. While that was largely driven by the longer-dated tenors that could rally as an economic slowdown is priced in, upward pressure on shorter-dated yields has also eased. Our concern is that investors may be underestimating either the difficulty of achieving price stability or the Fed’s commitment to it.

This is not to say that the U.S. – and global – economy will prove impervious to tightening. The economic outlook has indeed become more challenged. Driving our view is synchronized – albeit not coordinated – tightening across nearly all major economies. In regions where the post-pandemic recovery never fully blossomed, policymakers face the daunting scenario of stagflation. As evidenced by the bond market’s reaction to the previous – and incredibly short-lived – UK government’s fiscal fiasco2, countries that run persistent deficits are at acute risk as the cost of financing these imbalances increases.

The end of an era

Rising real interest rates likely harken the closing chapter of the decade-long run of financial repression where borrowers could feast on cheap and readily available debt financing. Looking forward, we believe both corporations and governments will be scrutinized more closely with respect to their ability to sufficiently cover their debt obligations. While the path to this destination is proving rocky, we think the end result will likely be a more efficient capital transmission mechanism where investors will be fairly compensated for the risks they choose to bear when participating in financial markets.

When the economic history books on the early part of the 21st century are written, an undeniable conclusion, in our view, will be that over a decade’s worth of quantitative easing failed to stimulate inflation and robust economic growth. Rather, it was the fiscal blowout accompanying the pandemic that finally caused prices to accelerate. But policy makers are now facing the unintended consequences of their largesse. This is especially true in regions that must continue to hike rates even as stagflation risks rise, and in the U.S., where the Fed’s laser-focus on backward-looking labour market data is likely to result in recession at some point in the near future.

Still, this year’s resetting of interest rates at considerably higher levels has given bond investors the opportunity to again benefit from the characteristics that have historically been the hallmark of a fixed income allocation: steady income, diversification from riskier asset classes, and – depending on how effectively the market has priced in future upward moves in interest rates – capital preservation. We believe the first two tenets have arrived but are more circumspect on the latter, as we believe that central banks have more work to do in taming inflation. We expect slowing growth and cooling inflation to be uneven, and this should create opportunities to increase allocations to geographies where policymakers are able to hit pause on monetary tightening.