Green AI

AI has certainly created a buzz over the past couple of years. While a lot of attention has been focussed on Nvidia, the global poster child for the AI sector, there has been a raft of cascading effects that have trickled down to related industries. An obvious one is data centres.

According to McKinsey, data centre capacity in the US alone is expected to double to 35GW by 2030 from 17GW in 2022. To put that in perspective, this is approximately equivalent to the entire installed capacity of Malaysia and up to 9% of US generating capacity. In terms of global electricity production, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that data centres worldwide used up to 460TWh of electricity in 2022 (equivalent to France, or ~2% of global production) and could be as high as 1,000TWh by 2026 (equivalent to Japan today).

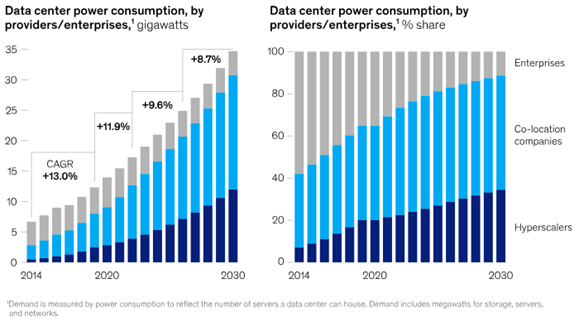

Global data centre industry power consumption forecasts

Companies like NextDC were already benefiting from high demand for their services. However, the ever-increasing digitisation of society is expected to see a supercharging of data requirements driven by AI advances. Consider the use of ChatGPT. This technology consumes up to ten times the electricity that a standard Google search does. The need to process vast quantities of data from multiple sources has resulted in evermore powerful processing units. In Nvidia’s case, newer GPUs like the B100 use up to 1,200W, or about three times that of the earlier A100 unit. So, while the efficiency may also increase, i.e., data per watt, absolute power consumption is skyrocketing as more users engage with this technology.

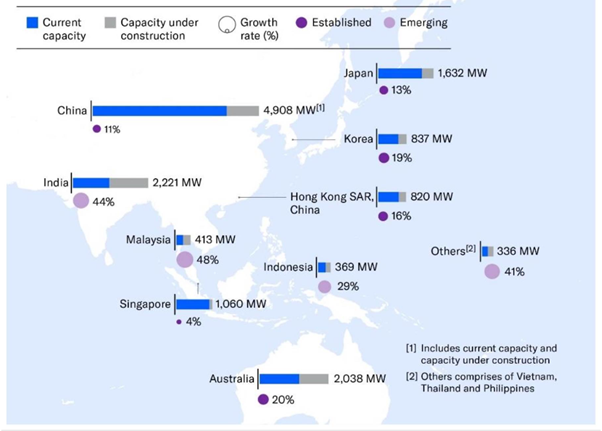

Current Asia Pacific data centre capacity and planned growth

This in turn leads us to a less obvious derivative of AI and digitisation in general – power supply as the critical enabling factor for these advances in technology, including cooling technology. The issue of power supply was recently raised by NextDC’s management and reported in the local press (e.g., The Australian Financial Review, 28 May 2024). At the company’s recent annual results presentation, the CEO referred to the growing size of potential contracts in Australia of at least 100MW and alluded to new data centres being up to 500MW in size versus their current maximum of around 300MW at S4. Outside Australia, individual, planned data centres now exceed 1GW capacity, e.g., Oracle is looking at a potential centre of this size in the US.

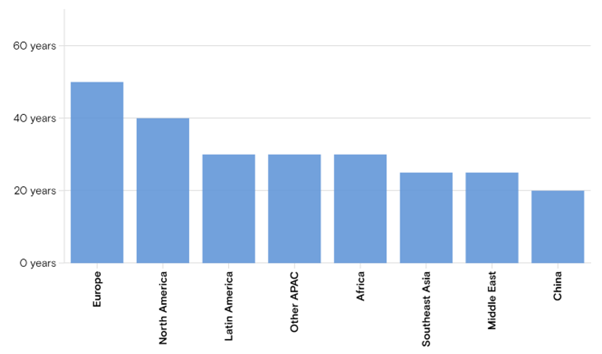

Whilst there is currently adequate capacity for new data centres, the looming problem is in the vastly divergent rates of technology adoption by the population and the planning, permitting and construction of new power supply. For data centre companies that are planning for indicated future demand, there is clearly a concern that their need for incremental power is a bridge too far for the grid as it stands. In addition to grid capacity, grid age is a concern in mature markets. Analysis by Goldman Sachs points to Europe as being particularly vulnerable with an average grid age of 50 years and hence additional investment is needed to support a larger, more intensive power draw.

Average age of Electricity grids around the world

Beyond access to additional raw power, another challenge with the growth of AI and data centres globally is the expanded grid transmission needed. Not only do more renewables require very expensive and politically fraught expansions of transmission grids into (wind and solar) regions previously not serviced by existing grids, the grids themselves are rapidly aging, especially in developed economies.

Nuclear again provides an elegant solution to this grid challenge, via co-location. We are starting to see data centre owners co-locate new planned facilities with a power source, eliminating the need for more grid transmission. Alongside proposing a 1GW plant, Oracle is reported to have floated the idea of building three Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) to power it. Elsewhere, Amazon purchased a US$650m data centre in March 2024 that is adjacent to a 2,500MW nuclear power plant, which provides electricity to the centre.

Nuclear is increasingly attractive to the data centre industry because it is an exceptionally reliable source of baseload power – a must for data centres – and helps them tackle the problem of CO2 emissions. If SMR’s become a viable technology, they are in turn more attractive due their small size and relative quick construction, and there are fewer issues with the wider grid.

On the issue of CO2, data centres have indeed caught the eye of ESG analysts as companies report more detailed data. For example, Google revealed that its carbon emissions grew 48% over the five years ending 2023 to over 14Mt, driven largely by computing intensity to support its AI data centres. The emissions profiles of data facilities are an area of concern for many of these companies, who buy offsets to reduce their carbon footprint or supplement their energy needs with renewable power.

However, it is not just the data centre industry that is looking to nuclear energy to solve the twin problems of large power draw and lower emissions profiles. Steelmakers, cement manufacturers, chemicals companies and refiners have proposed SMR solutions to their CO2 problems. For example, DOW Inc plans to replace gas generators with an SMR to become carbon neutral by 2050. Steel makers in Italy and cement companies in India are also investigating nuclear power and SMRs to decarbonise their operations without compromising on their power needs. Even some Australian miners such as Lynas Rare Earths believe that nuclear could be a viable option to power some of their remote mining sites using future SMR technology.

While the world works towards renewable solutions to permanently reduce CO2 emissions, nuclear energy is being resurrected on a global basis as a key part of the solution to climate change. The principal reason for this renaissance is its role as the only base-load source of zero emission power available. For this to happen the world will need a lot more uranium. The challenge, however, is that the historic chronic underinvestment in the mining side of the industry means that meaningful new uranium supply will be absent from the market until at least around 2030 in our view.

In light of this absence of new production we prefer those companies that are already in production, such as Boss Energy (BOE) and Paladin Energy (PDN). Both companies are now producing yellowcake and beginning to generate cash sales. In the case of Boss, it is ramping up to ~2.5Mlbs p.a. (plus up to 0.5Mlbs p.a. from the Alta Mesa mine in Texas) while Paladin will produce around 6Mlbs p.a. from the Langer Heinrich mine in Namibia.

With the term price of U3O8 sitting at about US$80/lb, Boss and Paladin can make healthy returns given guidance on cash costs of US$30-40/lb. However, if demand projections are correct and there is a significant shortfall in uranium supply over the next several years, then current producers are extremely well-placed to benefit. We saw the same dynamic at play with Pilbara Minerals when the lithium price spiked on a strong rebound in demand for lithium.

While the rise in the uranium term price to US$80/lb represents a significant increase from the low US$30s/lb four years ago, we note that on an inflation adjusted basis, previous price spikes have been as high as US$200/lb. We are not predicting that this will occur but as the rise in data centres show, the demand for power is not going down, and in this environment, global industry is looking for stable, low CO2 power supply.

How Australia deals with this problem remains to be seen. Internationally, however, nuclear is increasingly being seen as an integral part of the power supply solution. For this reason, we retain an exposure to Boss and Paladin anticipating increased cash flows as sales ramp-up into a strong pricing environment.

Author: David Haddad, Principal and Portfolio Manager.